Alvin Kallicharran’s Test debut century

Shan Razack

shanrazack@gmail.com

Monday, December 14, 2009 at 1:41 AM

New Zealand’s first tour of the Caribbean in 1972 produced an unenviable record-the first by an international team to end without a result in any of the first-class matches. It is true that, even with the inevitable frustration of drawn matches, there several days when the cricket was tense and interesting. On the whole, however, the tempo of cricket was slow.

Yet, for all these considerations, the main reason for what the headline writers aptly termed ‘Bourda Boredom’ was the attitude of the players themselves principally, Turner, Jarvis and Congdon. One could understand their desire to lay a sound foundation once the West Indies had declared at 365 for seven after an hour of the third day. Once this had been achieved subsequent tactics were completely inexcusable.

Turner, who had scored 259 on the same ground the previous week in the territorial match against Guyana, simply refused to take the slightest risk. It was his fourth double-century of the tour but, for all his runs there, he will never be kindly remembered by the Guyanese. Turner’s four double-centuries equaled a record established in 1930 by England’s Patsy Hendren for a West Indian tour. Congdon at one stage, had consecutive centuries in four matches when he was finally lbw to the new off-spinner Tony Howard-now manager of the beleagued West Indies team, and a One Test wonder- aiming through mid-wicket, he batted 11 ¾ hours and faced 762 deliveries. Jarvis, it must be admitted, had not played an innings of any consequence on the tour before this one. He was slower than his partner (182 in nine hours off 551 balls) but, in many ways, less stodgy.

If the openers were playing for records, they certainly achieved their objective. Their partnership of 387 was the highest by a New Zealand pair of any wicket in first-class cricket and the highest in tests against the West Indies. It was the second best opening stand in Test history, falling only 26 runs short set by Vinoo Mankad (231) and Pankraj Roy (173) for India against how ironically, New Zealand at Madras in 1955-56.

Turner’s score was his best in first-class cricket, as was Jarvis’s. Turner’s was also a ground record for Tests, beating West Indies prolific batsman Clifford Roach’s 209 against England in 1930.

Congdon approached his innings with even less enterprise than the two openers had done. His undefeated 61 lasted four hours and included only two boundaries (against bowlers such as Greenidge, Kallicharran and Rowe). His declaration, one felt, was forced on him only because of the economical approach of Charlie Davis who, in couple of overs just after lunch on the final day, brought light relief to the small crowd by mimicking the bowling styles of Gibbs, Morgan, Howard and even his country man, Sonny Ramadhin! When Turner was eventually caught at cover off Holford late on the fourth afternoon, the match and all of us present had already lost interest. By then, surely, New Zealand was in no danger of defeat. As if to add to the suffering, Fredericks and Greenidge proceeded to play with the same careful approach as the New Zealanders for the rest of the day and added 86 off 40 overs.

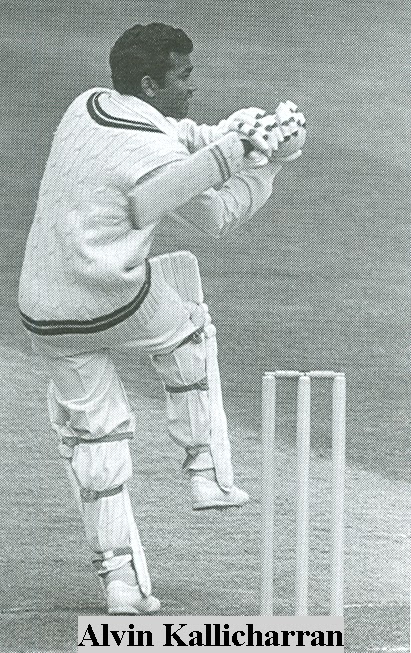

New Zealand’s brilliant fielding lifted their game. Vivian, Burgess, Jarvis and Hastings were particularly brilliant in the outfield cutting off dozens of runs with their diving saves and sure hands- reminds one of Carl Furlong of Trinidad. Vivian’s throw from the deep compared with any ever seen in the West Indies. Observers rated the team alongside the 1952-53 Indians as the best combination to tour the West Indies since the war. And bottle throwing from a section of the crowd after the run out of Lloyd. Despite the big scores by Turner and Jarvis, the best innings was played by our own diminutive Alvin Kallicharran, the young Guyanese in his first Test match.

Kallicharran who had made 54 runs against New Zealand, playing for the President’s X1 and then followed-up with a superb 154 and 51 versus New Zealand at Bourda was one of the four newcomers in the West Indies team- Clive Lloyd coming in for the first time in the series, the off-spinner Tony Howard and the opening batsman Geoffrey Greenidge making their debuts. Kallicharran came to the wicket late on the first day after Lloyd’s run out. By the time, the West Indies had not fared as well as had been hoped, being 178 for four. Fredericks had been unusually restrained for 41 before edging a catch to first slip; Greenidge, forced into the unaccustomed role as stroke maker, flashed at a wide ball and paid the penalty after an impressive half-century in his first Test innings; Rowe, never certain, was bowled.

At the time of his dismissal, Lloyd (43) seemed to be moving from third to top gear. The lanky left-hander had been strangely omitted from the first three Tests and had proved the folly of their ways to the selectors and the Guyanese crowd by two tremendous centuries in the preceding territorial match. His home crowd was preparing itself for another exposure innings when he hit the ball from Howard hard to mid-off and set off for the run. Davis did not agree with Lloyd’s judgment, followed the course of the ball and was surprised to see his partner on him when he turned. Lloyd never bothered to try to regain his ground. Within 10 minutes, the crowd’s disappointment at the loss of a local hero was reflected in a bottle-throwing incident- the second at Bourda- principally from the north-east corner of the ground, which held up play for 20 minutes. The players had to leave the field, Lloyd came to the broadcasting box to appeal for calm and, after 20 minutes, played was resumed in a tense atmosphere. Fortunately, the incident did not develop into anything like the previous bottle-throwing disturbances in the Caribbean.

When the match did continue, Davis, against whom feelings were vented, did have to remain in his hotel for the night under management instructions. Kallicharran’s first few minutes in Test cricket, therefore, had to be played out in this type of situation.

On the following day, Kallicharran had the further frustration of waiting until 20 minutes after lunch before he could resume because of rain. Lightening, they day, does not strike twice, but in the case of ‘bottle throwing at Bourda’it certainly did. Over fifty years ago, in 1954, my dad took me to see my First Test match there I was fortunate to witness the first of the bottle-throwing in the West Indies-England match

Cliff McWatt of BG and J.K. Holt Jr. of Jamaica were leading a rearguard action for the West Indies in the third Test. Batting with determination and obviously intent in getting the West Indies back into the game, they had added 99 respectable runs for the eight-wicket when disaster struck. McWatt was unfortunately run out for 54 and “Badge” Menzies made no hesitation in raising his finger. There was no doubt McWatt was out, but his brave innings had inspired hope of a West Indies revival, so when “Badge” gave him marching orders, a section of the crowd reacted badly. One man threw a bottle unto the field, and then, as if by some given command, a rain of bottles littered the field, forcing the English team to run-off.

It was sometime before the field could be cleared and at the end of the day, “Badge” had to be escorted to the pavilion after some spectators’ hurled insult, at the hapless man afterwards. By tea, Kallicharran had lost Davis, caught behind cutting, and Sobers offering a casual shot and was easily caught off the same bowler, Taylor. At 244 for six, Kali had only Holford, Findlay and the bowlers remaining. Holford, however, was of great assistance in Kalli’s quest to reach three figures. Kallicharran immediately attacked the previously tight New Zealand bowling. His confidence grew as a result and the partnership added 61 in even time, before Holford was leg before playing defensively to Congdon. Going into the third day, Kallicharran had 59 to his credit, and there and then his class was most evident. Realizing he had only a limited time to bat, he added the 41 needed for his century in an hour with a succession of superb shots all around the wicket, before Sobers declared. Overall, he batted for four hours, 18 minutes and struck a lofty six over long on off Howard and seven fours. At that point the match had died a natural death.

There is one gentleman who is still around who witnessed the Test match.

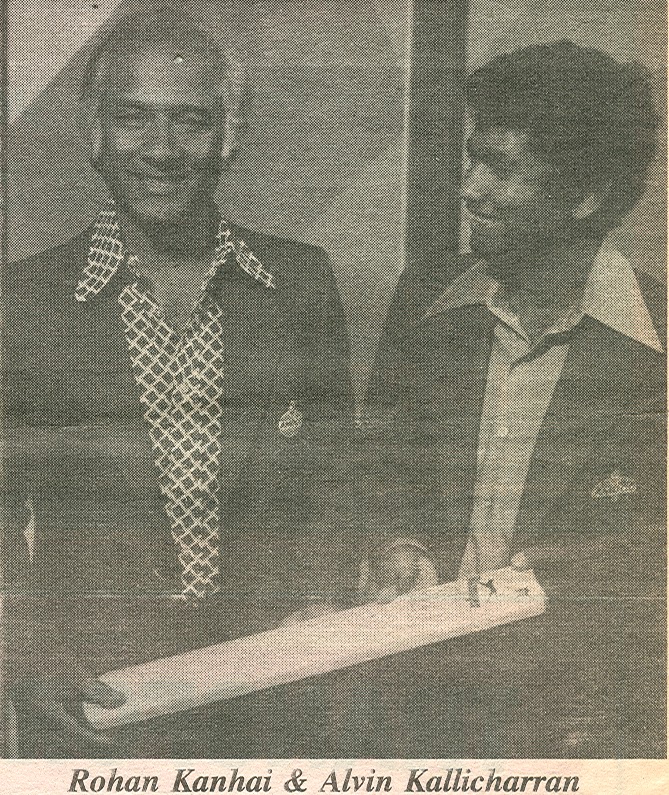

Isardat Ramdehol, a former Port Mourant all-rounder and vice-captain and opening batsman of the first- ever Berbice schoolboy cricket team against Demerara was at Bourda in 1972, and saw every one of Kalli’s runs scored. This is how he described it: “My eyes filled …when he was at naughty, nervous 99 and then reached 100! I cannot forget the ease with which he lifted Howard, the left-arm New Zealand spinner over mid-wicket for a towering six. The world was looking at a player who was to bring grace and charm to batting as his fellow colleague from Port Mourant, Rohan Bholalall Kanhai brought music to it.”

The main interest among the public on the final day was whether Glen Turner could equal Sobers’s world-record Test score of 365 not out. As it turned out, he fell well short. Just before lunch, trying to work Howard’s straight ball off middle and leg to the on side, he was LBW. His 259 was exactly the same as he had made in his previous innings against Guyana, being his best first-class score. He batted for 113/4 hours, hit 22 fours and faced 762 deliveries. The rest of the play was of mere statistical interest. Howard picked up his second wicket by bowling Burgess between bat and pad and Congdon eventually declared at 543 for three. The total was the highest ever by New Zealand in Test cricket, and the highest ever made in a Test match at Bourda.

Fredericks and Greenidge rounded off the match without changing its character in any way, their 86 coming off 40 overs. Yet, apart from the actual result, there was a great deal to make the outlook for the immediate future optimistic. Principally, the emergence of a number of outstanding young players was particularly heartening. Rowe, the Jamaican right-hander and Kallicharran, the Guyanese left-hander, made the most impressive debuts imaginable. The former became the first batsman ever to score a double and a single century in separate innings of his first Test; the latter immediately recorded two successive centuries after he gained his place in the fourth Test team. Both were in their early twenties and both batsmen were in the true West Indian mould, possessing all the strokes and able and willing to play them.

Their showing vindicated the West Indian selector’s decision not to recall the veteran Rohan Kanhai for the series, although it could not excuse the way in which it was done without so much of a thank-you to Rohan Bholalall Kanhai for his long and distinguished service to the West Indies.

No comments:

Post a Comment